75 Years Later: Remembering the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944

On Sept. 9, 1944, the Miami Weather Bureau detected a small disturbance to the northeast of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean.

By the time it reached New Jersey five days later, it had become a Category 3 hurricane, racing up the coast across Stone Harbor, Avalon and Sea Isle City, and leaving behind widespread damage and flooding.

Seventy-five years later, this storm, named the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944 by the Miami Weather Bureau, still ranks as one of the deadliest hurricanes in U.S. history. As it intensified, it claimed 390 lives, of whom all but 46 perished at sea, including 248 on a U.S. Naval destroyer off Florida.

New Jersey was one of the hardest-hit states: nine people lost their lives from drowning or flying debris, in Atlantic City, Long Beach Island and Sea Isle City. The state had the highest number of injuries (320) and destroyed homes (463), and fourth-highest number of damaged homes (3,066), behind Rhode Island’s 5,525, according to the National Weather Bureau.

At the time, the United States was embroiled in World War II, and gas and food rationing were still in effect. Yet, the local citizens were hopeful that the war would soon come to an end and were encouraged by the rebound of summer tourism. Little did they realize that the small disturbance near the Leeward Islands was growing stronger by the hour, soon to become a major hurricane that would leave large swathes of Cape May and Atlantic counties in tatters.

After its detection by the Miami Weather Bureau, the growing storm headed for the United States. On Sept. 11, it stalled for eight hours off Miami, leaving meteorologists guessing as to which way it would go. When it began to move again, it turned northward, grew to a 500-mile radius and passed Cape Hatteras on Sept. 12. Moving parallel to the coastline, the storm caused severe flooding as it pushed tremendous amounts of water inland, with winds gusting to 125 mph. The storm surge reached 9.6 feet, with waves of up to 40 feet pounding the shore.

When the hurricane reached New Jersey on Sept. 14, passing about 100 miles offshore, it had already been raining across the state for three days. Winds began to tear apart most of the fishing piers and boardwalks in Cape May County. The Stone Harbor boardwalk, constructed in 1916, was a wooden structure 25 feet wide that extended for more than a mile from 83rd Street to 106th Street, and did not survive the storm. Mayor John Biggs watched a large section of the boardwalk ride the crest of a gigantic wave up and over the top of a house, eventually coming to rest on First Avenue.

Aside from the boardwalk, Stone Harbor was spared the worst of the hurricane. Although there was flooding, most property damage was limited to the ocean side of the borough.

In Avalon, the Red Cross had to rescue people trapped in their homes by high water. Telephone and utility poles were washed away, cars were stranded, and roads became impassable.

Large sections of the fishing pier that connected with the Avalon boardwalk at 32nd Street and extended 385 feet into the ocean were swept away by the storm, eventually to be rebuilt in 1946. Sections of the circa-1913 boardwalk, which had extended a full two miles from 8th Street to 32nd Street, also were destroyed.

Sea Isle City took a beating. At its north end, nearly all homes were washed away into the marshes when the ocean met Ludlam Bay.

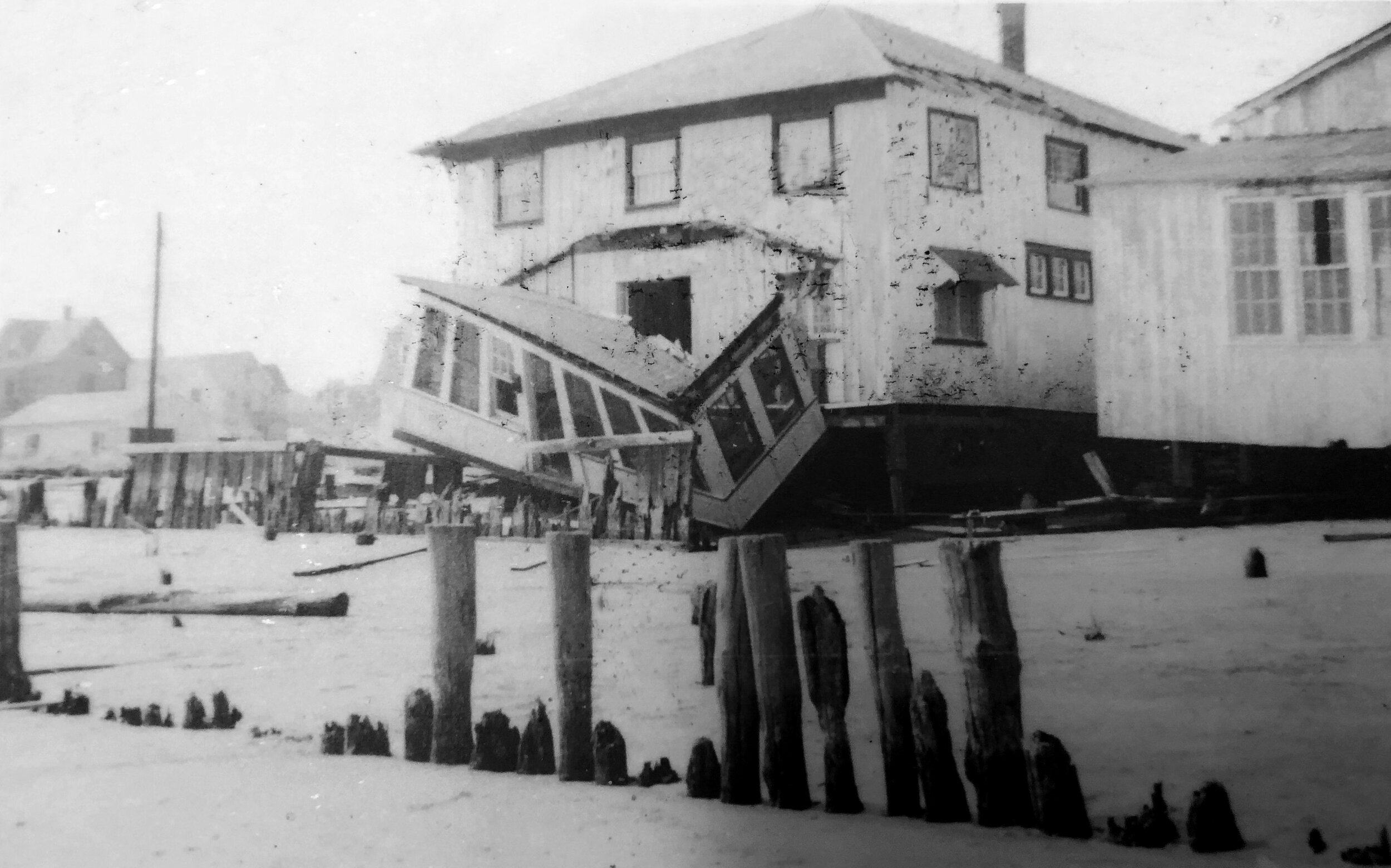

The Sea Isle boardwalk was mangled, stacked like kindling in front of the popular tourist destination, The Excursion House, with a large section carried away down Landis Avenue by the storm surge. The middle part of the fishing pier was washed away, and rock jetties at 33rd and the beach were strewn with lumber from obliterated structures.

The Excursion House suffered damage to its first-floor shops and restaurants, but amazingly remained largely intact despite its oceanfront location.

Roofs were lifted off homes, garages floated off, and homes were split in two. The Brotman Apartments on the beach at 39th Street crumpled over on their damaged foundation; the Sea Spray Hotel lost the walls of its first floor, while the Kress Restaurant collapsed down on its front wall.

Terrified residents and service people tried to flee the wind and the water. Public Service bus driver Bill Keyes had been trying to reach Sea Isle, but the storm surge flooded the bus, and he was forced to climb out and hang onto a telephone pole. He later swam to a nearby retreat house, where he was rescued by priests.

Private duty nurse Caroline Nick left the beachfront home of her employer but was swept away by the powerful water and drowned. Her body was later found covered in sand and debris not far away.

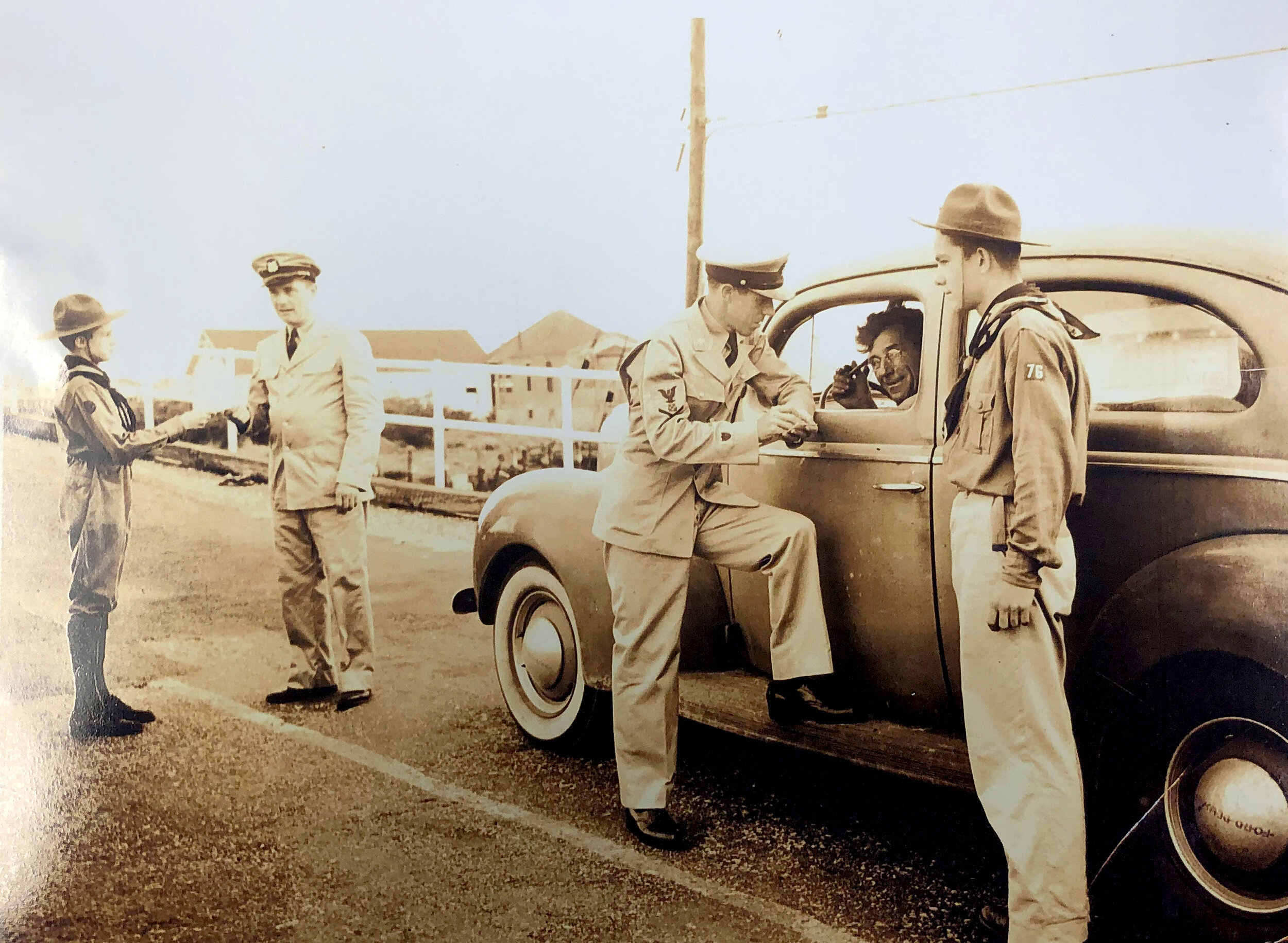

Looting began the following day, and the Coast Guard and police closed off the town, with all vehicles stopped at the Sea Isle Bridge to verify residence. Round-the-clock patrols to stop looting were implemented. Gov. Walter Edge asked the federal government for funding for storm damage, but ultimately none was received. Back then, most families and businesses were uninsured, and so had no financial help for disasters.

In the aftermath, state officials said the hurricane caused $36 million (in 1944 dollars) in damage to New Jersey. It left Atlantic and Cape May counties in ruins.

Because of World War II, most newspapers did not lead their front pages with storm coverage, instead focusing on the action in the Pacific theater.

The New York Times, for instance, gave the hurricane a one-column story on the left side of the front page, entitled, “Hurricane Tears Destructive Path 500 Miles on Coast; Jersey and Long Island Towns Hit Hard.”

Ruth Griesback, a Stone Harbor resident and docent at the Stone Harbor Museum, has vivid memories of the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944, viewed from her family’s summer home on 18th Street in North Wildwood.

“I was 5 years old, but I remember it like it was yesterday,” she says. “My cousins and I were on the front porch watching the storm as rocking chairs were blowing off the porches across the street. We were in awe of the sight, as everything happened so fast. When I turned my head around to look down the street towards the ocean and boardwalk – we were about five houses from the beach – I saw this huge wave go under and over the boardwalk. The ramp to the boardwalk exploded with boards flying so high in the sky I was frozen for an instant until I saw the wave gushing down our street. We all screamed and ran inside – a sight I’ll never forget.”

While most people who lived through the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944 are no longer with us, written accounts can be found in local history museums, such as the Sea Isle Historical Museum, the Stone Harbor Museum, and the Avalon History Center.

“I learned the Lord’s Prayer that day, spending the day and most of the night in the attic,” recalled Barbara A. Veilleux, an Atco resident who spent her seventh birthday in Townsends Island and wrote about her experience for The Press of Atlantic City. “We watched our neighbor Fred’s house float out to sea and sink. We watched items float by and planned a treasure hunt for the following morning. Praying and holding hands with my sister and my grandmother in that attic will be something I will always remember.”

Sea Isle resident George Phillips wrote in a remembrance for the Sea Isle Historical Museum: “Dr. Dealy had just removed my appendix, and I sat in my bedroom on the third floor of Busch’s in Townsends Inlet and watched the houses wash up on the street.”

Says Florence LaRosa: “It was very frightening. We could see the waves breaking on the boardwalk from our house on 43rd Street. I had a 3-month-old sister at the time, and my parents had to get sterilized water for her from the Red Cross that was set up at Cronecker’s.”

By Sept. 16, the local cleanup was in full swing. The National Weather Bureau, in its Monthly Weather Review publication, credited prompt dissemination of hurricane warnings by news agencies with the evacuation of the public from threatened areas, which saved many lives. It was a far cry from today’s computerized tracking of coastal storms, but at the time was considered revolutionary. And fortunately, Seven Mile Beach and Sea Isle City rebuilt, and recovered … until the next big storm arrived in 1962.