The Ride of a Lifetime: Andy Polovoy Reflects on 50 Years in the Bridge-to-the-Beach Bike-A-Thon

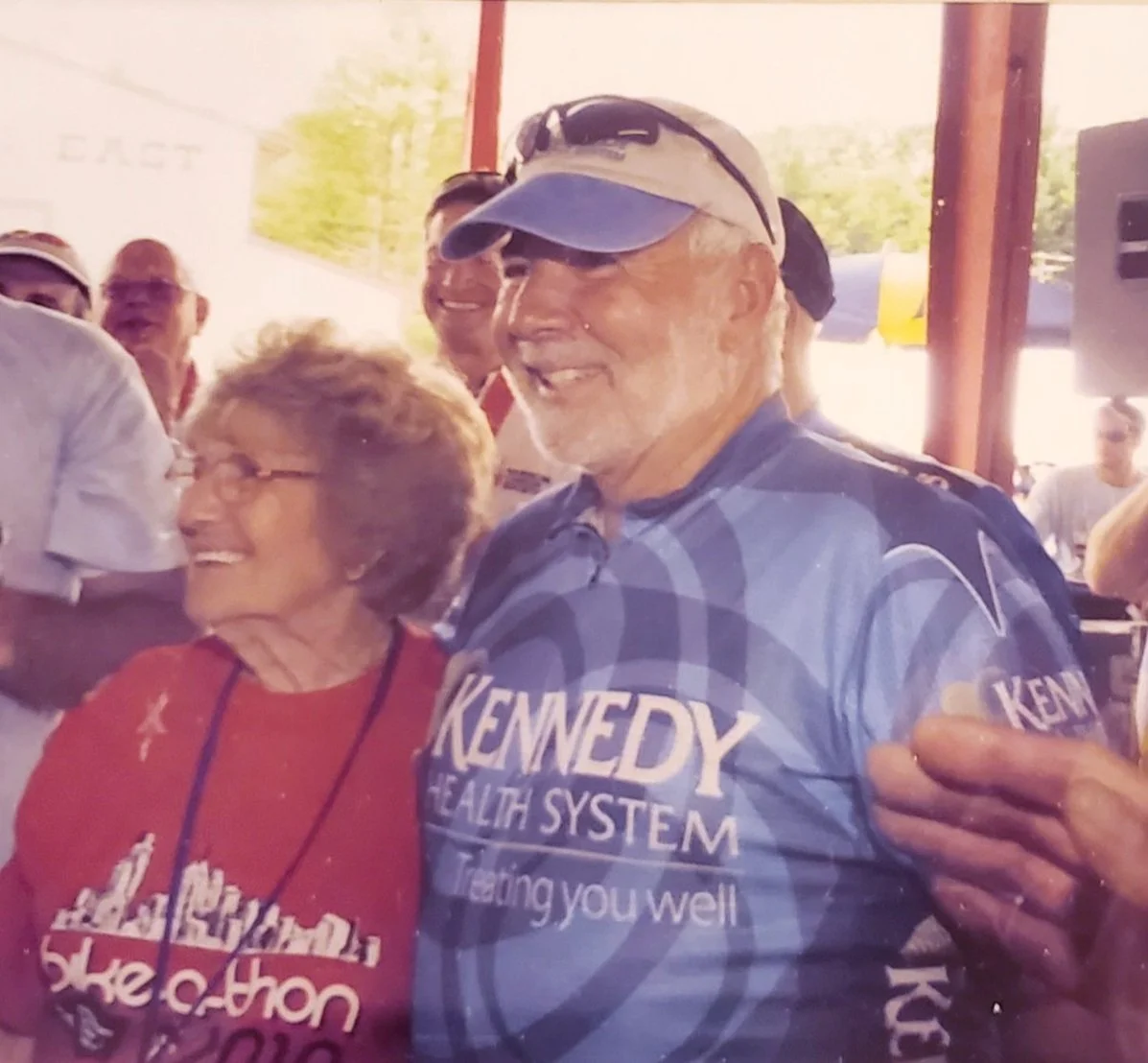

Andy Polovoy (second from right in both photos) with the Kennedy Health team before a long ride, and with the Jefferson Health team before an American Cancer Society Bike-A-Thon.

For Andy Polovoy, it’s not only the ride of a lifetime, but the ride that bridges one.

His life journey from Philadelphia to soon-to-be full-time Sea Isle City resident neatly curls around one of the most dynamic charity events in the United States: the American Cancer Society’s annual Bridge to the Beach Bike-A-Thon.

Polovoy was 26 when he took part in the first one. He is 76 now and his involvement in the 50th on June 12 meant completing all five decades with an event that has raised more than $30 million for cancer research. It routinely raises more than $1 million a year now and usually attracts 2,000-3,000 riders, cycling from the Ben Franklin Bridge to Bader Field in Atlantic City, about 66 miles.

An optional side loop through the Pinelands makes the journey 100 miles. Polovoy has ridden them both, and, in the service realm, has done the full loop: organizer and elder statesman, rider, cancer survivor, volunteer, top fundraiser, and team captain.

Andy Polovoy with mother Marie Bavier when she received a medal as the oldest living cancer survivor at an ACS Bike-A-Thon.

Following the 50th, he was honored on stage for being a 20-year committee member, a 20-year leader for orchestrating the cooperation of bike shops, and a 50-year participant (48 as a rider, two as a volunteer following hip replacements).

Polovoy was applauded. And when it was asked whether anyone in attendance had ridden that long, someone remarked, “I wasn’t even born yet when he started.”

“I was taken back by it all,” Polovoy says. “It was exhilarating to see so many survivors on stage. The fact that we have been able to do this fundraising and help people celebrate more birthdays is gratifying. Their stories and what we’ve done is a little cog in the wheel to help bring about more birthdays, hopefully longer life.”

The extra price of bad weather conditions was a reminder about the sacrifice participants make. A downpour accompanied the 2022 Bike-A-Thon, probably the first in about 15 years.

It was a rare way to mark five decades.

Polovoy began riding in 1972 to support people he didn’t know. He cycled Sunday to honor his late mother, Marie Bavier. She was diagnosed with cancer at 72, won the fight, and was 97 when she died of heart failure last September.

She participated with her son in the Bike-A-Thon for 25 years, coming up from Florida every year to volunteer.

“Once I saw what the ride did, the money it raised, I thought that was gratifying by itself,” Polovoy says. “But then after my mother got colon cancer and survived, and then I got skin cancer four years ago and survived, you realize what a community this is.”

Riders are linked not only with loved ones lost, but in the resolve to find cancer treatments that will one day save others.

Says longtime Bike-A-Thon chairman Mark Feinman: “People today benefit from the work of others done between 2010 and 2015, and people a few years from now will benefit by what cancer research is doing now. I am the beneficiary of work that was done in 1990s and early 2000s.”

Feinman credits his own recovery from bladder cancer in part to early detection.

“Through the years of understanding what cancer is about I can tell you that someone diagnosed today has an increased chance of surviving because of all the groundwork in research over the decades,” he says.

“So, yes while your heart will skip a beat and there will be fear and uncertainty about how to go forward, the truth is there is no better time in history to hear those words ‘You have cancer’ than right now.”

And that’s why the Bike-A-Thon throng has varied viewpoints on a similar goal: to look back to honor loved ones; to fight back against the disease; and to pay it forward to give the next generation an edge.

As he misses his mother, Polovoy thinks about his own evolution to the shore.

“Basically, I came here in 1984 and never left,” the retired Verizon supervisor says from his home at 56th Street and Sounds Avenue. “My friends and I rented a house on 39th Street for 15 years. We rented the whole summer.

“But the guy we were renting from was retiring, so one day I had nowhere to go. Fortunately, I was able to buy a house [in 1999] and stayed here in the summer. Shortly, it will be my permanent residence.

“I always loved it here. I had friends that would bike with me down to Wildwood or up to Ocean City, it all depended upon the wind. The music, the restaurants and the people have kept me here.”

Polovoy spent a lot of time here with his mom, with whom he ironically forged a deeper tie because of cancer.

“My mother became a big part of the Bike-A-Thon,” he says. “She served as a volunteer at the finish line in Atlantic City for so many years. She was an integral part of the end of the ride.

“One year she was honored as the oldest survivor of cancer in a ceremony with thousands of people there. I know that meant a lot to her.

“She told her story about how she didn’t want to die from cancer, and she didn’t.”

His mother was a fixture when she visited the home that will now fulfill Polovoy’s goal of living at the shore. When his Philadelphia house sells, he will be here all the time.

“When she came around here, the people loved her,” Polovoy remembers. “They asked after her. This was a special place for her.”

Before she died, his mother gave him a stunning emotional gift one afternoon.

Polovoy had barely known his father Andrew, who died at age 37 in 1959. One day last September, Marie informed him that she’d never been on a tram ride.

He took her right down to 16th Street in Wildwood.

“While we’re there, the Fralinger String Band was on the Boardwalk, so she got out and was doing the Mummers Strut with them, enjoying herself,” he says, smile broadening. “And up on the Boardwalk right there, she asks me where Magnolia Avenue was. I told her it was in the center of town.

“ ‘There,’ she told me, ‘is where I met your father.’

“And on their first date, he took her to the Starlight Ballroom, for dancing.

“I hadn’t known that story. I asked my siblings if they knew it. Nobody did. That had never come up until that moment. I will always cherish that day.”

A couple of weeks after that, his mom was gone.

Polovoy chuckles, recalling her involvement with the Bike-A-Thon. Before coming up, she’d inquire whether they had gotten her T-shirt, which all volunteers receive.

That made this rendition of it more poignant for Andy. It’s the first time in some 25 years that she wasn’t with him.

“It’s very strange to be doing it this year without my mom,” he says. “She loved being part of this. We spoke every day.”

Polovoy incorporated those feelings into the community nature of the Bike-A-Thon, which takes about seven hours to complete, between the ride and the closing ceremonies. He led the WMMR team down to Atlantic City.

“The overall experience is exhilarating,” he says. “One of my buddies sings the national anthem. He is a veteran. When you start the bike ride, you go over the Ben Franklin Bridge and it’s so majestic. We lead off the ride with cancer survivors and the others follow. You have all the jerseys, all the colors, there is music playing. You hear ‘Rocky’ at the start.”

When the event concludes at Bader Field, it’s a gathering of cancer survivors, their loved ones, of people still battling. It’s an outpouring of love, affection, and hope.

“The end of the ride is real rewarding,” he notes. “You come into Bader Field and you are cruising around the whole event. You see all the tents, the stands, the welcoming committees, etc. You see the food trucks, the beer garden and all the people, who make it as warm and welcoming as they can.”

Polovoy’s involvement with big causes doesn’t end with the cancer Bike-A-Thon.

He’s part of a similar event for multiple sclerosis that goes round-trip from Cherry Hill to Ocean City in the fall. It’s two days, 150 miles.

Polovoy has done that one for 32 years. His bike, it turns out, is a vehicle for giving back, and it’s a symbol.

He’s been, in one form or another, riding from Philadelphia to the shore most of his life.